- Home

- Preston Paul

We Saw Spain Die Page 3

We Saw Spain Die Read online

Page 3

Langdon-Davies made every effort to present a more realistic view to a British audience. Since first visiting Catalonia in 1920, and living there during the years 1921–22 and 1927–29, Langdon-Davies had been an enthusiastic student and advocate of Catalan culture. His book, Dancing Catalans, published in 1929, reflected his admiration for the humanity and egalitarianism that he believed were the essence of social relations in rural Catalonia. The persecution of the Catalan language and popular culture under the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923–30) intensified Langdon-Davies’ sympathies for Catalan nationalism. Unsurprisingly, the establishment of the democratic Second Republic on 14 April 1931 seemed to him to promise a freedom for the region that he loved.

On 6 August 1936, barely three weeks after the military coup, he arrived at Puigcerdà on the Spanish border on a second-hand motorcycle with his fifteen-year-old son, Robin. After leaving Robin with Catalan friends in Ripoll, he went on to Barcelona as a special correspondent of the liberal London daily, the News Chronicle. Between 11 August and 7 September, on an almost daily basis, he wrote articles in which he tried to put the disorder and church-burnings into their historical context. He believed that King’s consular staff were contributing to an atmosphere of panic among British citizens in Barcelona: ‘Many of these lost their heads completely, and one can sympathise with them, seeing that the British officials supposed to look after them completely lost theirs.’ He claimed that Norman King ‘became so childishly terrified that he refused to send a conservative newspaperman a car to go to the local airport, saying that it was too dangerous, and that he would not risk the lives of his chauffeurs. This was in mid August when everyone else was settling down to normal existence.’19 The man in question was almost certainly the correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, Cedric Salter.20

Thereafter, Langdon-Davies went to Valencia, Madrid and Toledo before returning to England on 19 September. He used the material gathered as the basis for lectures on behalf of the relief organization, Spanish Medical Aid, and for the book Behind the Spanish Barricades which he wrote in barely five weeks in the intervals between his lectures. During his brief time in Spain, Langdon-Davies was quickly convinced that the British policy of non-intervention was disastrous for both the Spanish Republic and for Britain. This brought him into direct conflict with the views being propounded by Norman King. In September 1936, he vainly visited the Foreign Office in London in an attempt to counteract the apocalyptic view emanating from right-wing sources about the Catalan President, Lluís Companys, and of the situation in Barcelona. Langdon-Davies mistakenly underestimated the scale of the killing in Barcelona, and this led to officials checking his figures with Norman King. The Consul gloated and he seized the opportunity to brand Langdon-Davies as a Communist, which he certainly was not.

Despite his sympathy with the Republic, Langdon-Davies did not try to pretend that revolutionary violence did not exist, but he made an effort to understand what lay behind it. In the case of the shooting of thirteen fascist sympathizers in Ripoll, the town where he left his son, he faced a grave moral dilemma:

as I thought of those superb, simple-hearted working men and peasants in overalls, organising as best they could to keep the Moorish invasion from saving Christianity by killing Spanish Christians; as I thought of their gentleness, their zeal, their courtesy, and how in spite of it all they had been moved to get up and kill thirteen fairly harmless men, my heart hardened against those who had brought to Spain the most horrible atrocity of all, civil war.

The blame, he concluded, lay with ‘those who let loose the supreme horror of civil war’.21

Langdon-Davies was one of the first to confront a problem that would bedevil the work of all those foreign correspondents who tried to write sympathetically about the uneven struggle of the Republic against fascist aggression and to awaken the governments of the democracies to the threat that faced them. As wild fantasies about Communist conspiracies and Muscovite skulduggery proliferated, he wrote:

To the many readers who quite sincerely believe in the insincerities of our philo-fascist press I say, ‘I beg of you to believe it possible that you have been misled. Read and imagine things in terms of human men and women; of simple folk, insulted and injured, whose hope of an end to the Dark Ages has been destroyed by rebellion subsidised from abroad. If you saw your family doomed to the conditions of the Spanish peasantry and workers, would you need Moscow gold to make you cling to the little you had and fight for a little more? Remember all that you have heard of the age-long tyrannies of Spain; do you realise that a victory for the Rebels means their re-imposition on the remnant left alive?.22

Within barely two months of the military coup, Langdon-Davies had put his finger on one of the greatest problems facing the most serious journalists and commentators. The early days of the terror, particularly in Barcelona, would colour subsequent perceptions and stand in the way of transmission of more profound truths about what was happening in Spain. Newspapermen in Spain would face the same problems as foreign correspondents in any war: local censorship and physical danger. However, in addition they faced the prejudices of editors who did not want to hear either about the plight of the Republican population or about the blind complacency of the Western decisionmakers. Revolutionary violence fed the representation of a bloodstained Republic which made it possible to ignore the fact that the fascist powers were using Spain to alter the international balance of power against the democracies.

The British journalist Cedric Salter complained that to discuss the real issues in Spain was regarded in ‘polite society’ as ‘not in quite the best of taste’. On one occasion, he sent to a London paper a powerful story about an old man caught trying to smuggle a few potatoes into Barcelona for his family. In the ensuing altercation, both a policeman and the old man were shot. The story was not printed and Salter was given the explanation that:

Newspapers are mostly read at breakfast, and there is nothing better calculated to put a man off his second egg and rasher of bacon than reading a story forcing him to realize that not so very far away there are people dying for a handful of potatoes. If one newspaper puts him off his breakfast he takes pains to buy another one. That we naturally wish to avoid.23

At the end of the conflict, the American newspaperman Frank Hanighen, who had briefly served as a correspondent in Spain, edited the reminiscences of several of his companions. He commented that:

Almost every journalist assigned to Spain became a different man sometime or other after he crossed the Pyrenees… After he had been there a while, the queries of his editor in far-off New York or London seemed like trivial interruptions. For he had become a participant in, rather than an observer of, the horror, tragedy and adventure which constitutes war.24

The well-travelled American correspondent Louis Fischer similarly noted that:

Many of the foreign correspondents who visited the Franco zone became Loyalists, but practically all of the numerous journalists and other visitors who went into Loyalist Spain became active friends of the cause. Even the foreign diplomats and military attachés scarcely disguised their admiration. Only a soulless idiot could have failed to understand and sympathize.25

Journalists of every political hue hastened to the Spanish Republic and were permitted to carry out their daily tasks. The only ones excluded were the representatives of the official media of Franco’s allies: Hitler, Mussolini and Salazar. In contrast, the military rebels admitted to their zone only those journalists whom they believed to be sympathetic to their cause – those from Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Salazar’s Portugal and the correspondents of the conservative press of the democracies. Of course, some of the latter were actually highly critical of the military atrocities that they saw, but were prevented by a fierce censorship from publishing them until they could write memoirs after leaving Spain.

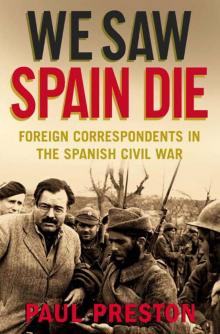

Nearly one thousand newspaper correspondents went to Spain.26 Along with the professional war correspondents, some hardened veteran

s of Abyssinia, others still to win their spurs, came some of the world’s most prominent literary figures: Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Josephine Herbst and Martha Gellhorn from the United States; W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and George Orwell from Britain; André Malraux and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry from France. A few arrived as committed leftists, rather fewer as rightists, and plenty of those who spent brief periods in Spain were simply jobbing newspapermen.

However, as a result of what they saw, even some of those who arrived without commitment came to embrace the cause of the beleaguered Spanish Republic. Underlying their conversion was a deep admiration for the stoicism with which the Republican population resisted. Vernon Bartlett of the News Chronicle was impatient with the many political committees that had to be dealt with in the Republican zone. Nevertheless, he commented later ‘My love of comfort and an easy life and my anger with the committees which did their best to rob me of them had taken away most of the enthusiasm for the Spanish Government with which I had left London. But when one saw the odds they had to face one’s sympathy revived.’27 In Madrid, Valencia and Barcelona, the correspondents saw the overcrowding caused by the endless flow of refugees fleeing from Franco’s African columns and from the bombing of their homes. They saw the mangled corpses of innocent civilians bombed and shelled by Franco’s Nazi and Fascist allies. And they saw the heroism of ordinary people hastening to take part in the struggle to defend their democratic Republic.

In trying to capture accurately what they saw, observation became indignation and sympathy became partisanship. As Louis Delaprée, the correspondent of Paris-Soir, wrote a mere eight days before his death in December 1936:

What follows is not a set of prosecutor’s charges. It is an actuary’s process. I number the ruins, I count the dead, I weigh the blood spilt. All the images of martyred Madrid, which I will try to put before your eyes – and which most of the time defy description – I have seen them. I can be believed. I demand to be believed. I care nothing about propaganda literature or the sweetened reports of the Ministries. I do not follow any orders of parties or churches. And here you have my witness. You will draw your own conclusions.28

It was not just a question of correspondents describing what they witnessed. Many of them reflected on the implications for the rest of the world of events in Spain. What they saw and what they risked were perceived as portents of the future that faced the world if fascism was not stopped in Spain. Their experiences led them into a deep frustration and an impotent rage with the blind complacency of the policy-makers of Britain, France and America. They felt, in the words of Martha Gellhorn, that:

the Western democracies had two commanding obligations: they must save their honour by assisting a young, attacked fellow democracy, and they must save their skin, by fighting Hitler and Mussolini, at once, in Spain, instead of waiting until later, when the cost in human suffering would be unimaginably greater.29

Accordingly, they tried to convey what they saw as the injustice of the Republic having been left defenceless and forced into the arms of the Soviet Union because of the Western powers’ short-sighted adoption of a policy of non-intervention.

Many journalists were driven by their indignation to write in favour of the loyalist cause, some, like Jay Allen and George Steer, to lobby in their own countries, and in a few cases even to take up arms for the Republic. Without going so far, many of the correspondents who experienced the horrors of the siege of Madrid and the inspiring popular spirit of resistance became convinced of the justice of the Republican cause. In some cases, such as Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn and Louis Fischer, they became resolute partisans, to the extent of activism yet not to the detriment of the accuracy or honesty of their reporting.30 Indeed, some of the most committed correspondents produced some of the most accurate and lasting reportage of the war.

Like many others, Fischer found his emotions deeply engaged with the cause of the Republic. Comparing the impact of the Russian Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, he wrote:

Bolshevism inspired vehement passions in its foreign adherents but little of the tenderness and intimacy which Loyalist Spain evoked. The pro-Loyalists loved the Spanish people and participated painfully in their ordeal by bullet, bomb and hunger. The Soviet system elicited intellectual approval, the Spanish struggle brought forth emotional identification. Loyalist Spain was always the weaker side, the loser, and its friends felt a constant, tense concern lest its strength end. Only those who lived with Spain through the thirty-three tragic months from July 1936 to March 1939 can fully understand the joy of victory and the more frequent pang of defeat which the ups and downs of the civil war brought to its millions of distant participants.31

Frank Hanighen believed that ‘The Spanish war ushered in a new and by far the most dangerous phase in the history of newspaper reporting.’32 He underlined the dangers faced by correspondents – at least five were killed during the war, numerous others wounded. On both sides, correspondents faced danger from snipers, the bombing and strafing of enemy aircraft. On both sides too, there were difficulties to be overcome with the censorship apparatus, although what could be irksome in the Republican zone was downright life-threatening in the rebel zone. More than thirty journalists were expelled from the Francoist zone, but only one by the Republicans. The rebels shot at least one, Guy de Traversay of L’Intransigeant, and arrested, interrogated and imprisoned about a dozen more for periods ranging from a few days to several months.33

There was physical risk from shelling and bombardment in both zones, although the rebel superiority in artillery and aircraft meant that it was greater for those posted in the Republic. Moreover, the close control exercised over correspondents in the rebel zone kept them away from danger at the front. Within the rebel zone, there were of course enthusiasts for Franco and fascism, and not just among the Nazi and Italian Fascist contingent. Nevertheless, the British, American and French Francoists were a minority. Many more of those who accompanied Franco’s columns were repelled by the savagery they had witnessed with the rebel columns. Those in the rebel zone were kept under tight supervision and their published despatches were scoured to pick out any attempts to bypass the censorship. Transgressions were punished by harassment, and sometimes imprisonment and expulsion. Accordingly, they could not relate what they had seen in their daily despatches and did so only after the war, in their memoirs.

The correspondents in the Republican zone were given greater freedom of movement, although they too had to deal with a censorship machinery, albeit a much less crude and brutal one than its rebel equivalent. However, they faced another problem not encountered by their right-wing colleagues. Given that the bulk of the press in the democracies was in right-wing hands, pro-Republican correspondents found publicizing their views often more difficult than might have been expected. It was ironic that a high proportion of the world’s best journalists and writers supported the Republic but often had difficulty in getting their material published as written.

In the United States, the debates over the issues of the Spanish war were especially embittered. The powerful Hearst press and several dailies such as the Chicago Daily Tribune were deeply hostile to the democratic Republic even before the military coup of 1936. Jay Allen, for instance, would be fired from the Chicago Daily Tribune because his articles provoked so much sympathy for the Republic. There were cases of the Catholic lobby using threats of boycott or the withdrawal of advertising to make smaller newspapers alter their stance on Spain. This had happened even before the outbreak of war. In late 1934, James M. Minifie went to report on the situation in the Basque Country for the New York Herald Tribune. Before leaving Paris, he was warned that ‘the Power House’ – the Roman Catholic hierarchy in St Patrick’s Cathedral – was putting the heat on advertisers to insist that only ‘reliable’ news of Spain be printed: ‘It worked by indirection, rarely telephoning the management, but making it clear to advertisers that they should not imperil their immortal souls or their pocket-bo

oks by dealing with supporters of leftists, pinkos, and radicals.’34

Such pressures intensified with the outbreak of war in Spain. Dr Edward Lodge Curran, President of the International Catholic Truth Society, boasted in December 1936 that his control of a large sum in advertising business permitted him to change the policy of a Brooklyn daily from pro-Loyalist to pro-rebel. Other more liberal newspapers were subjected to pressure to prevent the publication of pro-Loyalist news. Herbert L. Matthews, the meticulously honest New York Times correspondent, was constantly badgered with telegrams accusing him of sending propaganda. In 1938, the paper lost readers when the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Brooklyn helped organize a campaign specifically aimed against Matthews and his reporting.35 In Spain for the North American Newspaper Alliance, Hemingway also had cause for frequent complaint about his material being changed or simply not used.36 He, Matthews and others believed that material deemed sympathetic to the Spanish Loyalists was edited or even omitted. In fact, both the cable desk and the night desk of the New York Times – effectively where it was decided what news would be printed – were manned by religious fanatics hostile to the Republican cause.37

We Saw Spain Die

We Saw Spain Die