- Home

- Preston Paul

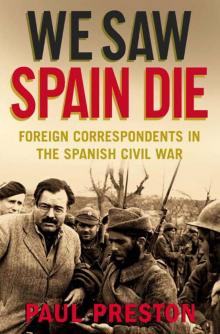

We Saw Spain Die

We Saw Spain Die Read online

WE SAW

SPAIN DIE

WE SAW

SPAIN DIE

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS IN

THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR

PAUL PRESTON

CONSTABLE • LONDON

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55-56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson, 2008

Copyright © Paul Preston, 2008, 2009

The right of Paul Preston to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-84529-946-0

eISBN: 978-1-78033-742-5

Printed and bound in the EU

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Part One: Say that We Saw Spain Die

1 The Wound that Will Not Heal: Terror and Truth

2 The Capital of the World: The Correspondents and the Siege of Madrid

3 The Lost Generation Divided: Hemingway, Dos Passos and the Disappearance of José Robles

4 Love and Politics: The Correspondents in Valencia and Barcelona

5 The Rebel Zone: Intimidation in Salamanca and Burgos

Part Two: Beyond Journalism

6 Stalin’s Eyes and Ears in Madrid? The Rise and Fall of 203 Mikhail Koltsov

7 A Man of Influence: The Case of Louis Fischer

8 The Sentimental Adventurer: George Steer and the Quest for Lost Causes

9 Talking with Franco, Trouble with Hitler: Jay Allen

Part Three: After the War

10 The Humane Observer: Henry Buckley

11 A Lifetime’s Struggle: Herbert Rutledge Southworth and the Undermining of the Franco Regime

12 Epilogue: Buried Treasure

Postscript: Love, Espionage and Treachery

Notes

Bibliography

Index

To the Memory of Herbert Rutledge Southworth (1908–99)

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to all those who have helped to make this book possible. In particular, I must thank those who generously helped me locate the diaries, letters and other papers on which the book is principally based: the Very Reverend Dean Michael Allen and his daughter Sarah Wilson, for giving me access to the papers of Jay Allen; Patrick and Ramón Buckley, for lending me materials relating to their father Henry Buckley; Charlotte Kurzke, for granting permission for me to use the invaluable unpublished memoirs of her parents Jan Kurzke and Kate Mangan; Carmen Negrín, for providing access to the papers and photographs held in the Archivo Juan Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria; Paul Quintanilla, for giving me access to the papers of Luis Quintanilla; and David Wurtzel, for providing me with the diary and other papers of Lester Ziffren.

I am also very happy to record the help of numerous librarians who helped me locate particular papers. For the good-humoured tolerance with which they dealt with my complicated requests regarding the papers of Tom Wintringham and Kitty Bowler, I am indebted to the Staff of the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, King’s College London. Similarly, I am immensely grateful to Andrew Riley and Sandra Marsh of Churchill College Cambridge Archives Centre for their enthusiastic assistance in locating the correspondence between George Steer and Philip Noel-Baker. Gail Malmgreen has, for many years, been unfailingly helpful regarding requests and queries related to the ALBA Collection of the Tamiment Library, at New York University. Kelly Spring of the Sheridan Library, Johns Hopkins University, helped in the location of the Robles papers. Natalia Sciarini of the Beinecke Library, Yale University, went the extra mile in helping find particular items relating to Josephine Herbst. Above all, I want to thank Helene van Rossum of Princeton University Library for help and perceptive advice above and beyond the call of duty regarding the voluminous papers of Louis Fischer.

I am fortunate in the specific help I received regarding particular chapters. This is especially true of the chapter on Mikhail Koltsov, for which I must express my immense debt to Frank Schauff, whose unstinting help with Russian sources was indispensable. Robert Service, Denis Smyth, Ángel Viñas and Boris Volodarsky all contributed with sage advice and saved me from many errors. René Wolf and Gunther Schmigalle provided invaluable assistance on the German dimension of Koltsov’s career. For the chapter on George Steer, I benefited from the generous help of Nick Rankin. I would also like to thank Christopher Holme of the Glasgow Herald for sending me material on his namesake who was with Steer in Guernica. For the chapter on José Robles, Will Watson generously shared his encyclopaedic knowledge of Hemingway in Spain, and José Nieto recounted his recollections of his conversations with John Dos Passos, Artur London and Luis Quintanilla. I was greatly stimulated by the enthusiastic response of Elinor Langer to my questions about Josephine Herbst. On the developments in the press office in Valencia, I benefited from the insights of Griffin Barry’s daughter, Harriet Ward. I was also helped by David Fernbach in relation to the role of Tom Wintringham and Kitty Bowler. In Madrid, the indefatigable Mariano Sanz González was as helpful as ever. Regarding matters connected with the International Brigades, I turned to Richard Baxell and was never disappointed. I am also indebted to Larry Hannant of the University of Victoria and Professor David Lethbridge at Okanagan College, British Columbia for their help in unearthing material about Kajsa Rothman.

Surviving protagonists are unfortunately now few. I was thus especially glad to be able to benefit from the memories of three people who were in Spain: the late Sir Geoffrey Cox, whose chronicles from besieged Madrid remain important historical sources; Adelina Kondratieva, who was an interpreter with the Russian delegation; and Sam Lessor, who fought with the International Brigades and, after being wounded and invalided home, returned to Spain to work for the Republican propaganda services in Barcelona.

Four friends made a big difference. I ended up writing the book in the first place as a result of an invitation from Salvador Clotas to contribute to the catalogue of the splendid exhibition about foreign correspondents in Spain organized jointly by the Instituto Cervantes and the Fundación Pablo Iglesias. A trip to Lisbon to take part in the inauguration of the exhibition brought me into contact with its curator, Carlos García Santa Cecilia. To meet someone who shared my enthusiasm for the subject was an exhilarating experience and helped convince me that I was not engaged in a totally lunatic enterprise. Will Watson read several chapters with hawk-eyed precision. Lala Isla, as always, has been a fount of affectionate encouragement and I am immensely grateful for her close and sympathetic reading of all the chapters. The generous advice of Soledad Fox on sources and archives in the USA has been crucial. Without her unstinting encouragement and advice, this book would have been infinitely poorer.

It is with great pleasure that I also thank Andreas Campomar, my publisher and friend, for his faith in the project.

Finally, I want to thank the two people who have influenced this book the most. The first is my friend Herbert Southworth, who was a participant in much of what follows. Many years of conversations and correspondence with him taught me much about the Spanish Civil War in general and in particular about the correspondents

with whom he had worked. The book is dedicated to him with deep gratitude for his friendship and his example. The other is my wife Gabrielle, who has always been my most lucid critic and reliable supporter. Her acute perceptions regarding the way in which unpalatable truths can be dismissed as bias have been an invaluable foundation for the book.

Illustrations

Every effort has been made to locate the rights holder to the pictures appearing in this book and to secure permission for usage from such persons. Any queries regarding the usage of such material should be addressed to the author c/o the publisher.

Henry Buckley and Louis Fischer in Barcelona, 1938. Courtesy of the Buckley family.

Jay Allen. Courtesy of the Reverend Michael Allen.

Lester Ziffren, Douglas Fairbanks and Juan Belmonte. Courtesy of Didi Hunter.

Sefton Delmer in Madrid. Courtesy of Felix Sefton Delmer.

Geoffrey Cox. Courtesy of the late Sir Geoffrey Cox.

Louis Delaprée. Courtesy of the Instituto Cervantes.

Arthur Koestler after his arrest in Málaga, February 1937. Courtesy of El País

Mikhail Koltsov and Buenaventura Durruti on the Aragón front at Bujaraloz, August 1936. Courtesy of EFE.

Ernest Hemingway, Communist General Enrique Líster, International Brigade Commander Hans Kahle and Vincent Sheean during the Battle of the Ebro. Courtesy of the Buckley family.

Mikhail Koltsov and Roman Karmen at the front outside Madrid, October 1936. Courtesy of the Instituto Cervantes.

Mikhail Koltsov and Maria Osten. Courtesy of the Instituto Cervantes.

Herbert Matthews and Ernest Hemingway in ‘the Old Homestead’.

Herbert Matthews, Philip Jordan and Kajsa Rothman visit Alcalá de Henares. © Vera Elkan Collection, Imperial War Museum (HU 71630).

Josephine Herbst meets the villagers of Fuentidueña del Tajo, April 1937. Courtesy of Elinor Langer.

Liston Oak watches the front with Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Cowles and Kajsa Rothman, April 1937. Photographed by Joan Worthington.

Claud Cockburn, founder of the satirical news-sheet, The Week and Comintern agent Vittorio Vidali. © Vera Elkan Collection, Imperial War Museum (HU 71569).

Virginia Cowles of Harpers’ Bazaar, autumn 1937. © Angus McBean.

Kajsa Rothman with a Swedish International Brigader. © Arbetarrörelsens Arkiv och Bibliotek, Stockholm.

George Lowther Steer with a group of French journalists, January 1937. Courtesy of George Steer.

Guernica after the German rehearsal for Blitzkrieg. Courtesy of Museo de la Paz, Guernica.

Jay Allen, Diana Sheean, Mrs Caspar Whitney, Juan Negrín, Muriel Draper and Louis Fischer discuss the display of Picasso’s Guernica at the Paris Exhibition, summer 1937. Courtesy of Carmen Negrín.

Louis Fischer with the Soviet and Spanish Foreign Ministers, Maxim Litvinov and Julio Álvarez del Vayo at the League of Nations, Geneva, December 1936. Courtesy of Carmen Negrín.

Tom Wintringham, Commander of the British Battalion of the International Brigades, with Kitty Bowler. Courtesy of Ben Wintringham.

Safe-conduct issued to Kitty Bowler by the Catalan government. Courtesy of Ben Wintringham.

Kate Mangan and Jan Kurzke, in the hospital in Valencia. Courtesy of Charlotte Kurzke.

Kate Mangan’s permission to attend a meeting of the Spanish parliament in Valencia on 30 September 1937. Courtesy of Charlotte Kurzke.

Luis Bolín. Courtesy of the Instituto Cervantes.

Clipping of L’Intransigeant ’s report of the murder of its correspondent, Guy de Traversay. Courtesy of the Instituto Cervantes.

Harold Cardozo, Victor Console and Jean D’Hospital on the Madrid front, November 1936. Courtesy of the Instituto Cervantes.

John Dos Passos, Sydney Franklyn, Joris Ivens and Ernest Hemingway in the Hotel Florida, April 1937. © Corbis.

Kajsa Rothman fund-raising for the Republic in Stockholm. © Arbetarrörelsens Arkiv och Bibliotek.

Juan Negrín and Louis Fischer at a meeting of the League of Nations, September 1937. Courtesy of Carmen Negrín.

Gerda Grepp, Nordahl Grieg and Ludwig Renn. Courtesy of Norges Kommunistiske Parti, Trondheim

Ernest Hemingway, Henry Buckley and Herbert Matthews surveying the Ebro, November 1938. Courtesy of the Buckley family.

Ernest Hemingway rows Robert Capa, Herbert Matthews and Henry Buckley across the Ebro, November 1938.

Constancia de la Mora recovering after the war. Photographed by John Condax. Courtesy of John and Laura Delano Condax.

Jay Allen, captured by the Germans. Courtesy of the Reverend Michael Allen.

Arturo Barea and Ilsa Kulcsar together in their British exile. Courtesy of Bruce and Margaret Weeden.

Herbert Southworth in Sitges, April 1984. Courtesy of Gabrielle Preston.

PART ONE

SAY THAT WE SAW SPAIN DIE

1

The Wound that Will Not Heal:

Terror and Truth

‘It was in Spain that men learned that one can be right and still be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own reward. It is this, without doubt, which explains why so many men throughout the world regard the Spanish drama as a personal tragedy.’

Albert Camus

When Spain’s Second Republic was established on 14 April 1931, people thronged the streets of the country’s cities and towns in an outburst of anticipatory joy. The new regime raised inordinate hopes among the most humble members of society and was seen as a threat by the most privileged, the landowners, industrialists and bankers, and their defenders in the armed forces and the Church. For the first time, control of the apparatus of the state had passed from the oligarchy to the moderate Left. This consisted of the reformist Socialists and a mixed bag of petty bourgeois Republicans. Together, they hoped, despite considerable disagreement over the finer details, to use state power to create a new Spain by curtailing the reactionary influence of the Church and the Army, by breaking up the great estates and by granting autonomy to the Basque Country and Catalonia. These hopes were soon blunted by the strength of the old order’s defences.

Social and economic power – ownership of the land, the banks and industry, as well as of the principal newspapers and radio stations – remained unchanged. Those who held that power united with the Church and the Army to block any challenges to property, religion or national unity. Their repertoire of defence was rich and varied. Propaganda, through the Right’s powerful press and radio networks and from the pulpit of every parish church, denounced the efforts at reform as the subversive work of Moscow. New right-wing political parties were founded and lavishly funded. Conspiracies were hatched to overthrow the new regime. Rural and industrial lock-out became a regular response to legislation aimed at protecting worker interests.

So successfully was reform blocked that, by 1933, the disillusioned Socialists decided to leave their alliance with the liberal Republicans and go it alone. In a system heavily favouring coalitions, this handed power to the Right in the November 1933 elections. Employers and landowners now cut wages, sacked workers, evicted tenants and raised rents. Social legislation was dismantled and, one after another, the principal unions were weakened as strikes were provoked and crushed – notably a nationwide stoppage by agricultural labourers in the summer of 1934. Tension was rising. The Left saw fascism in every action of the Right; the Right smelt revolution in every left-wing move.

On 6 October 1934, when the authoritarian Catholic party, the CEDA, entered the government, the Socialists called a revolutionary general strike. In most of Spain, it failed because of the swift declaration of martial law. In Barcelona, an independent state of Catalonia was short-lived. However, in the mining valleys of Asturias, there was a revolutionary movement organized jointly by the Socialist union, the Unión General de Trabajadores, the anarcho-syndicalist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo and, belatedly, the Communists. For nearly three weeks, a revolutionary commune h

eroically held out until finally the miners were reduced to submission by heavy artillery attacks and bombing raids co-ordinated by General Franco. The savage repression that followed was to be the fire in which was forged the Popular Front, essentially a re-creation of the Republican–Socialist coalition.

When elections were called for mid-February 1936, a well-financed right-wing campaign convinced the middle classes that Spain faced a life-or-death fight between good and evil, survival and destruction. The Popular Front campaign stressed the threat of fascism and demanded an amnesty for those imprisoned after October 1934. On 16 February, the Popular Front gained a narrow victory and thus shattered right-wing hopes of being able to impose legally an authoritarian, corporative state. Two years of aggressive rightist government had left the working masses, especially in the countryside, in a determined and vengeful mood. Having been blocked once in its reforming ambitions, the Left was now determined to proceed rapidly with meaningful agrarian reform. In response, right-wing leaders provoked social unrest, then used it in blood-curdling parliamentary speeches and articles, to present a military rising as the only alternative to catastrophe.

The central factor in the spring of 1936 was the weakness of the Popular Front government. The Socialist leader Francisco Largo Caballero had insisted that the liberal Republicans govern alone until the time came for them to make way for an all-Socialist government. He was mistakenly confident that, if reform provoked a fascist and/or military uprising, it would be defeated by the revolutionary action of the masses. So he used his power in the Socialist Party to prevent the formation of a strong government by his more realistic rival Indalecio Prieto. Mass hunger for reform saw a wave of land seizures in the south. Thoroughly alarmed, the Right prepared for war. A military conspiracy was headed by General Emilio Mola. The liberal Republicans of the Popular Front watched feebly as the terror squads of the growing fascist party, Falange Española, orchestrated a strategy of tension, its terrorism provoking left-wing reprisals and creating disorder to justify the imposition of an authoritarian regime. One such reprisal, the assassination on 13 July of the monarchist leader, José Calvo Sotelo, provided the signal for the conspirators.

We Saw Spain Die

We Saw Spain Die